Moca Attacks

1975 marks the start of the Chupacabras story, when stories of disappearing farm animals began to spread around the small town of Moca, Puerto Rico. Although the descriptions of the attacks and the monster differed greatly from the now-popular Chupacabra myth, the townspeople called the beast el vampiro de Moca (the vampire of Moca). Though this myth did not gain as much global popularity, it marks the start to the story of Chupacabra (Lewis).

Image Credits: Nelson Corales

First Sighting

In March 1995, the first sighting of the Chupacabra was documented, with eight sheep discovered killed during the night. Strangely, all the sheeps were drained of their blood, with three puncture wounds in their bodies. Though many attributed this attack to the actions of a Satanic cult, many Puerto Rican newspapers highlighted the story as an attack from the Puerto Rican bloodsucking monster (Than).

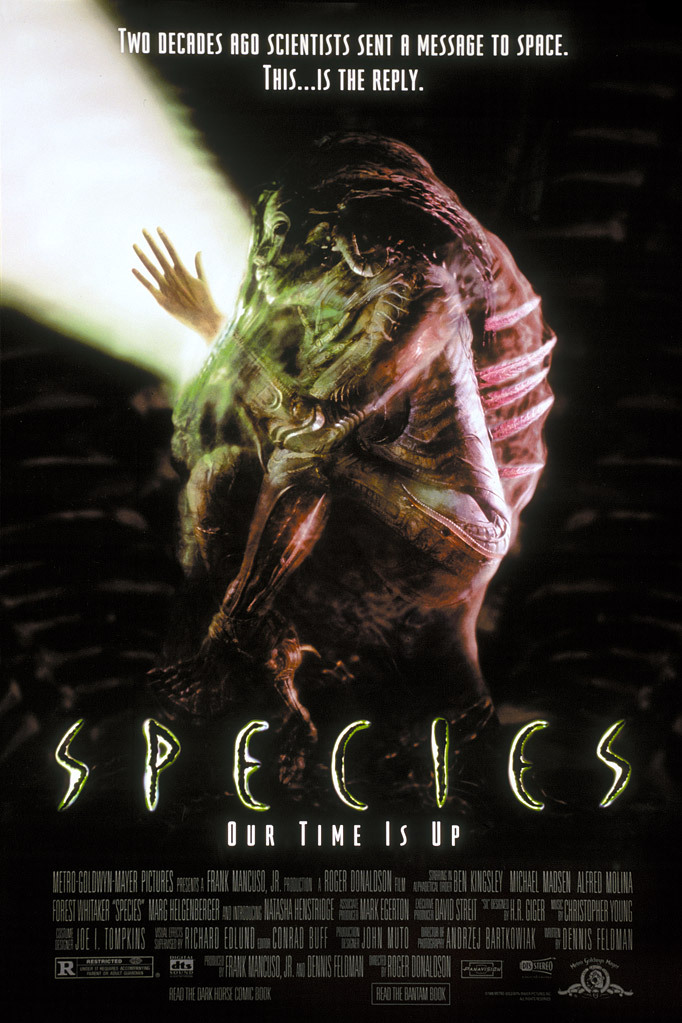

Species

Image Credits: Metro Goldwyn Mayer Studios Inc.

Shortly after the Chupacabra’s first attack, the science fiction blockbuster Species was released, a movie depicting an extraterrestrial monster Sil that terrorized humans. The movie was especially popular in the United States and Puerto Rico, and modern analysis of the Chupacabra myth shows that many of the Chupacabra’s characteristics and powers originate from depictions created within this movie (Lewis).

Madelyne Tolentino

Madelyne Tolentino is a supposed eyewitness credited with defining many of the characteristics that now make up the popular Chupacabra myth. Tolentino reportedly saw the Chupacabra up close one night in the town Canovanas, which she described as a scary, alien-like creature with spines on its back and greenish-gray skin feasting on the livestock. Her interview exploded in popularity across Puerto Rico and Latin American countries, and sparked a glowing global interest in the Puerto Rican cryptid (Diffee, Lewis).

Silverio Pérez

Though the Puerto Rico bloodsucker was growing in popularity, no name for it was yet popularized. This changed when the Puerto Rican comedian and actor Silverio Pérez took it upon himself to flesh out the myth. During a radio show in Puerto Rico, Pérez described his story seeing the monster, describing it as chupacabras, meaning goat sucker (Lewis).

Image Credits: Santos Torres

Cuero Attack

After a decade the myth of the Chupacabra began to die down, until the cryptid finally reached the US. After a suspected Chupacabra attack in the town of Cuero in Texas, the myth exploded into global popularity with multiple US news outlets describing the attacks. This time, the Chupacabra shifted from Tolentino’s depiction to that of a hairless wild dog, with fangs, claws, and a spinal ridge. This attack spawned global sightings of the monster ranging from Nicaragua to Iraq to even Japan (Diffee, Lewis).

Image Credits: Rene Library

Sarcoptes Scabiei

Inspired by the Cuero attack, biologist Barry O'Connor from the University of Michigan sought to study the existence of the Chupacabra by researching any natural biological explanations for the goat attacks. He credits the deaths to the parasite sarcoptes scabiei, which infects coyotes, causing fur loss and a rank odor similar to what eyewitnesses to the Chupacabra attacks described. He also described how the animals were greatly weakened by the parasite, causing them to attack livestock rather than wild rabbits and deers. To this day, O’Connor’s analysis stands as the most accepted scientific explanation for the Chupacabra myth (Lewis).

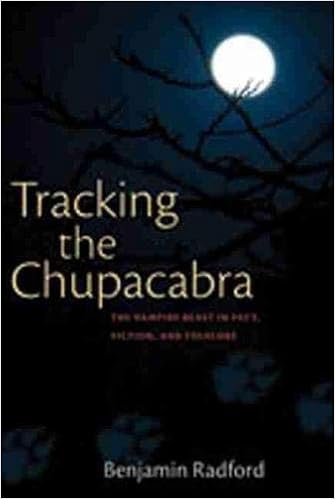

Tracking the Chupacabra

Image Credits: Benjamin Radford

The Chupacabra myth over the past one and a half decades culminated into Benjamin Radford’s book ‘Tracking the Chupacabra’, a five year investigation into the Chupacabra. The book contains all the information pertinent to the cryptid, including eyewitness testimony, interviews, and documentation of evidence (Lewis).

More importantly, the book describes the historical events that led to the creation of the Chupacabra myth, spurred on by the popularity of the Species movie and the introduction of a deadly parasite into a heavily agricultural economy (Wagenheim).